Fire Threats to Archaeological Sites: an Unexpected Theme

Can fires of all vegetation damage archaeological or cultural resources? Actually, fire always poses a threat to every human artefact, but when it comes to assessing the vulnerability of objects covered by the ground, so-called crown fires do not necessarily have the worst impact on objects that emerge from the ground or are underground.

In general, for various reasons, archaeological assets are not often associated with a fire risk. In reality, there are cases where artifacts made of non-combustible materials dating back hundreds or thousands of years are damaged by fires.

What temperatures does ground reach during a vegetation fire?

To understand how important the risk assessment that a vegetation fire poses to the archaeological heritage is, it is important to have data on the ground temperature that can be reached. In this regard an indication of the temperatures achieved by a land surface was provided by KC Ryan in his 1991 research article “Dynamic interactions between forest structure and fire behavior in boreal ecosystems“. According the article:

- 1,5 cm below: almost 500°C

- Mineral soil: up to 300 °C

- 4,5 cm above: more than 500 °C

- 3,0 cm above almost 500°C

These temperatures must be compared with the threshold temperatures of damage suffered by the individual materials that constitute the archaeological asset. In any case, it is evident that the levels of thermal exposure are always significant.

What are the most frequent damages?

(Image by Helt., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1658037c)

The damages to cultural heritage in a forest environment during a wildfire are categorized into three groups, incorporating aspects that highlight the importance of damages caused by firefighting operations during emergency response activities. Fires not only impact and destroy educational structures and tourist resources associated with these heritage contexts, but it is crucial to consider these factors when proposing guidelines for the restoration of the affected area.

- Direct Damages or Primary Damages: These are caused directly by high temperatures and the products and by-products of combustion. They are immediately observable, either with the naked eye or through analytical procedures. Examples include the total or partial destruction of organic matter and physical-chemical transformations (thermoclasticism, reddening, etc.) produced by lithic materials in architecture, archaeological structures, or those supporting rock art.

- Indirect Damages or Secondary Damages: These occur after the fire is extinguished and can recommence or accelerate over time for various reasons:

- Increased levels of alteration/erosion over time: The modification of the physical-chemical characteristics of materials during the fire makes them more susceptible to atmospheric and biological agents, accelerating processes like aging, decomposition, etc.

- Environmental modification: Loss of vegetation cover followed by precipitation leads to increased surface runoff and varying degrees of erosion, causing the loss and removal of archaeological layers. In extreme cases, this can result in mudflows that may destabilize or collapse architectural structures.

- Anthropogenic actions on the affected territory: Looting by opportunistic individuals taking advantage of the situation to remove objects from archaeological sites or damages caused during area restoration work, such as the removal of burnt wood or reforestation.

The Castilla y León case

An example of damage to cultural heritage caused by fires was published inthe #2 Bulletin of the Proculther-net Project with the article on “Forest fires and cultural heritage: protection strategies in Castilla y León”, written by Cristina Escudero. Although the short but detailed text does not directly concern archaeological assets, it is based on the general consideration that “Cultural Heritage exposed to the destructive effects of flames belongs to all the categories contemplated and to all the levels of protection established by law“.

The article, specifying that in 2022 the region suffered severe damage with over 80,000 hectares of forest burned and 173 cultural heritage sites damaged, explains that the damage affected different areas and types of heritage sites, including the monastery of Santo Domingo de la Batuecas (saved in extremis) and the monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos (evacuated). Basically, the article remarks that:

- Forest fires are a growing threat, especially in rural areas, with devastating consequences for lives, property, the environment and cultural heritage.

- Cultural heritage in rural areas is particularly vulnerable due to the lack of adequate policies that bridge the gap between urban and rural areas, leading to depopulation, abandonment of agricultural activities and increase in biomass fuel.

- This context favours the development of large forest fires (LFF), which are increasingly intense and difficult to control.

- Cultural heritage at risk includes different types: cultural heritage assets (BIC), inventoried assets, UNESCO sites, ethnographic heritage, traditional architecture, pilgrimage sites, architectural heritage, historic routes, industrial heritage and, above all, archaeological heritage of all ages, including rock art.

- It is essential to consider these assets not in isolation, but as part of a broader cultural landscape, intertwined with natural heritage and local communities.

Equally interesting is to understand what the response of regional government bodies has been to the need posed by the increased exposure to fire risk of cultural heritage vegetation. In particular, the response of the Region of Castilla y León has been articulated in the following actions:

- The Region established the Risk and Emergency Management Unit for Cultural Heritage (UGRECYL) in 2016, with a special focus on the protection of cultural heritage at risk from forest fires. UGRECYL focuses on disaster risk reduction and management strategies, using georeferenced databases to create risk maps and assess the vulnerability of cultural heritage. The Unit classifies damage to cultural heritage into three categories:

- Direct damage: caused by high temperatures and combustion products.

- Indirect damage: resulting from increased erosion and environmental alterations.

- Operational damage: produced by fire extinguishing operations.

- A fire monitoring and control protocol has been activated, integrating satellite information and cultural heritage databases.

A case of practical application of the organization and protocols adopted concerns the fire of the Navalacruz (Ávila, 2021). In particular, in this event:

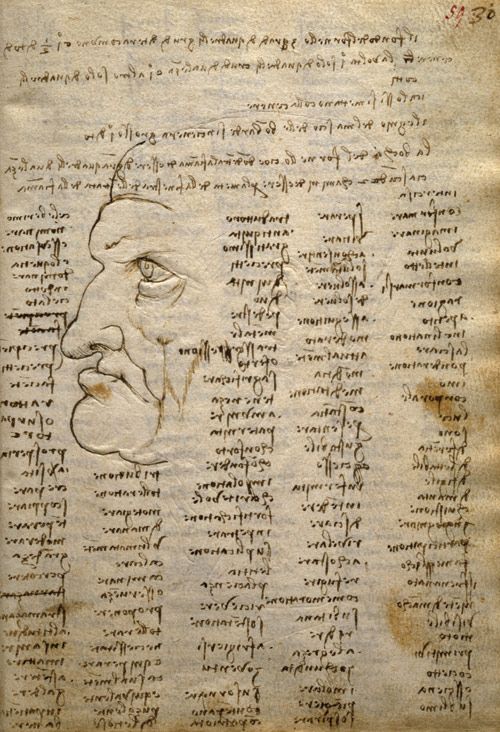

( https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2444405)

- The fire affected an area of 22,000 hectares, with 35 cultural assets identified, including the Malqueospese castle, the rock art of Las Chorreras and the archaeological site of Ulaca.

- UGRECYL collaborated with the Terra Levis group for a detailed damage assessment, including non-inventory assets and tourism infrastructure.

- The assessment considered several aspects: the significance of the asset, safety risks, primary damage (direct and operational), post-fire vulnerability and priorities for protection and recovery.

- Different types of damage were detected: from none to minor, moderate, severe and, in one case, the destruction of an ethnographic bridge.

- The methodology developed allowed us to obtain accurate information and plan recovery strategies, taking into account both the specific problems of cultural heritage and its role in tourism.

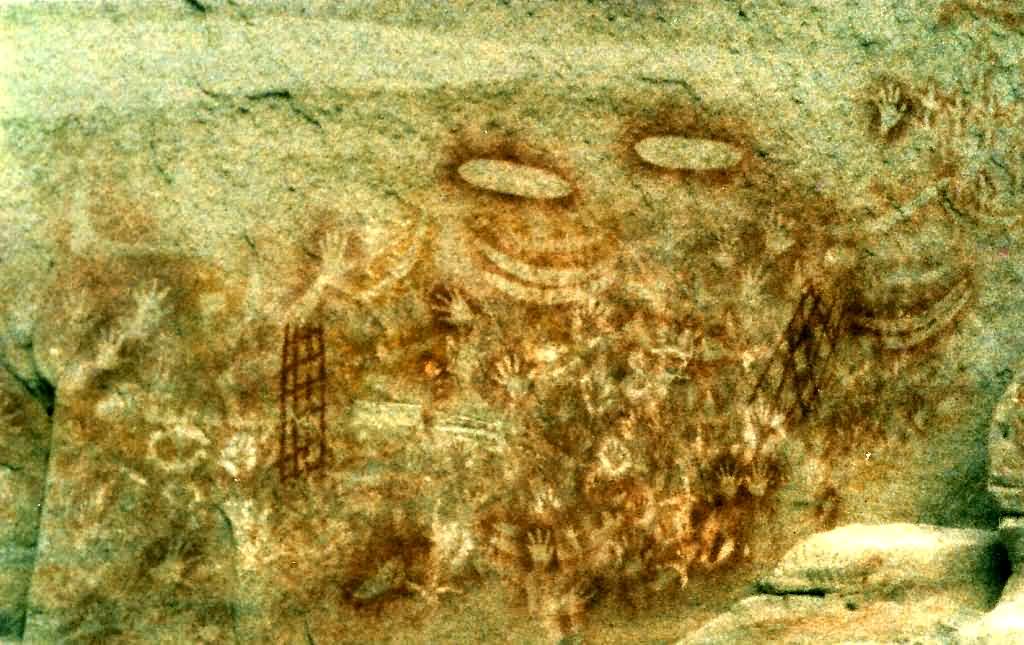

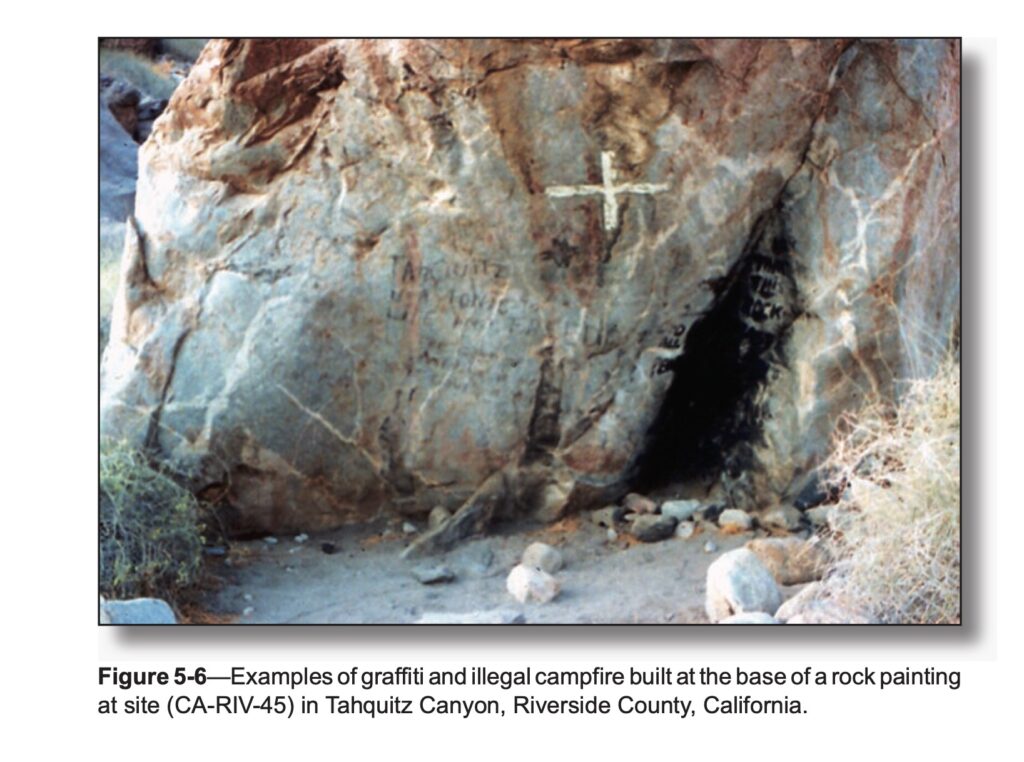

The Australian experience

In Australia many archaeological assets are destroyed or seriously damaged by fires which, very often (but not only) are due to vegetation. Emblematic in this regard is the case of the fire that damaged the ancient rock art of Carnarvon Gorge, Australia. The destruction of Baloon Cave occurred during the devastating 2018 Queensland bushfires, when the archaic rock was destroyed after the burning of a recycled plastic walkway triggered by the fire. The incident has prompted calls for the removal of all flammable structures at similar sites. Another threat to archaeological remains is vandalism and unintentional but illegal use of fire. This threat is well documented in the “Effects of Fire on Cultural Resources and Archaeology” USDA publication.

Another issue related to the threat of fire to archaeological assets is related to the various types of artifacts commonly found in historic sites and their susceptibility to fire damage. Chapter 5 of the USDA publication lists a number of different materials and the effects of fire on each:

- Leather: Items such as leather shoes, belts, and horse harnesses are found at historic sites. Over time they become dry and brittle and can become charred or completely consumed in fires.

- Rubber and Rubberized Objects: These are found at many historic sites, some dating back to the Civil War period. Rubber can ignite and wear away completely at low temperatures, such as those caused by grass fires.

- Plastic: Common in sites from the early 20th century onwards, plastic is used to produce various items such as toys, buttons and containers. Although different plastics have different melting points, most plastic objects would be affected to some extent by low-temperature fires.

- Wooden Artifacts: Wooden objects such as buckboards, Model T car seat frames, ox yokes, and ax handles are prevalent at historic sites. When displayed outdoors, they often have some rot, making them more susceptible to destruction by fire.

- Bones: Dry, porous bones will char in grass fires and be completely consumed in high-temperature fires.

- Shell Buttons: These buttons can discolor, flake, split along laminations, and eventually turn to dust when exposed to high-temperature fires. Similar effects can occur at lower temperatures, especially if the buttons are small and thin.

In summary, protecting cultural heritage from forest fires requires ongoing commitment, a collaborative and knowledge-based approach, and proactive action by all actors involved. It is essential to consider cultural heritage as an integral part of the landscape and local communities, integrating risk management at all stages, from prevention to response and recovery.

Learn more: