LiDAR and Cultural Heritage in Emergency Operations

The project STORM (Safeguarding Cultural Heritage through Technical and Organisational Resources Management) has been funded by the Horizon 2020 EU Program and aims at defining a platform that managers of cultural heritage sites can use in improving preparedness, managing emergencies and planning restoration of damaged buildings.

The project specifically considers risks that the cultural sites have to face from either long-term degradation (whose action is far slower than the typical applications of feedback controls), or extreme traumatic events (whose action is much faster). Their common nature is the climate change. So, the specific scope of the project is creating a technological platform that allows a systematic comparison between a real (measured) state and a desired theoretical state.

Assumptions are kept to the minimum possible level and the difference (the measured error signal), is the main input for whatever algorithm may be used to compute the action (input) that needs to be applied to the mitigation process to achieve the desired objective. So, in other words, reliable and up-to-date measures of the key risk variables are the base line for the STORM predictive model but also for the identification of better intervention actions in terms of restoration and conservation of original materials that will be the starting point for a long term mitigation strategies. As a consequence, needs take into account the use of a large number of sensors, in order to acquire the most useful data. For example, in the case of a progressive relative displacement of a structural beam of an ancient monument, over time comparison of periodical LIDAR based detection of the artefact overall 3D model can be used to detect the small differences in the beam’s position over time.

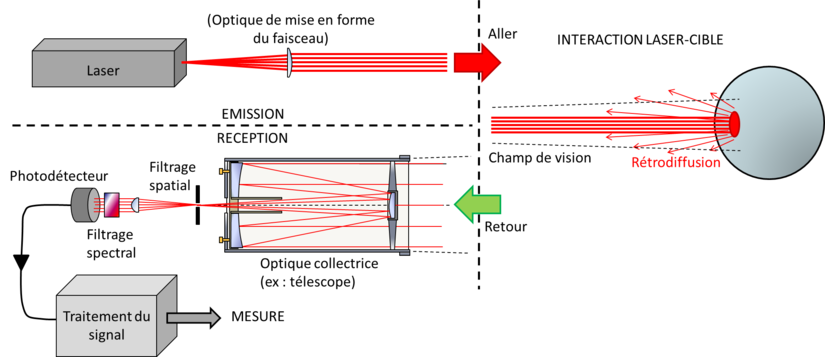

According Wikipedia, Lidar (also called LIDAR, LiDAR, and LADAR) is a surveying method that measures distance to a target by illuminating that target with a laser light. The name lidar, sometimes considered an acronym of Light Detection And Ranging (sometimes Light Imaging, Detection, And Ranging), was originally a portmanteau of light and radar. Lidar is popularly used to make high-resolution maps, with applications in geodesy, geomatics, archaeology, geography, geology, geomorphology, seismology, forestry, atmospheric physics, laser guidance, airborne laser swath mapping (ALSM), and laser altimetry. Lidar sometimes is called laser scanning and 3D scanning, with terrestrial, airborne, and mobile applications.

How Cultural Heritage can benefit of LiDAR (according STORM Project)

Based on such information a team of experts (structural engineers, archaeologists, geologists, restorers) will cooperate, in order to understand the causes and find the most adequate response. In this example, the action cannot be predetermined (nor taken automatically of course), but instead requires a careful and accurate cooperative design and planning of the action in order for it to be as effective and as unobtrusive as possible.

When a disaster occurs, general guidelines related to a wide range of events (e.g. flood, earthquake), existing for the specific site, must be dynamically adapted in near real time by ad-hoc team of experts in order to identify the most urgent recovery actions for the specific emergency. So, LIDAR sensors used for structural evaluation and track-changes of the artefact in terms of erosion monitoring as also for geomorphological assessment and mapping of the protected area can offer a valuable support to managers. Moreover, photogrammetric reconstruction by means of historical and contemporary aerial photography to track-changes can support when it comes to assessing the damages through time and forecast potential future threats

LIDAR equipment have been used until now mostly on movable supports, that are steadily placed on the ground to let an accurate record of data. More recently, RPAS devices have been tested as platform to be equipped with regular camera (high resolution RGB still pictures) for monitoring and mapping, Near Infrared camera and thermal and multispectral sensors or the localization and monitoring of buried structures, light-weight LiDAR for higher resolution 3D scanning. Such possibility has demonstrate its extreme importance during emergency situations: in fact, accessing parts of buildings in some cases can be difficult or can pose a severe risk to rescuers. During the rescue operations of the Central Italy earthquake of August 2016, RPAS mounted LIDAR have been used in many scenarios by the Italian National Fire Service and a complete report of such use hasn’t been published yet.

In which scenarios can LIDAR sensors prove to give data not replaceable by other sensors or any operational procedures? One of the first case is any natural or man-made threat that can damage the structures of heritage buildings. Suppose that, after an earthquake, in an ancient masonry buildings fixtures are identified. Even if, in general, it is possible to track the evolution of a fixture in a building, in the larger buildings it is actually impossible to be certain that a damage has been produced by a specific event.

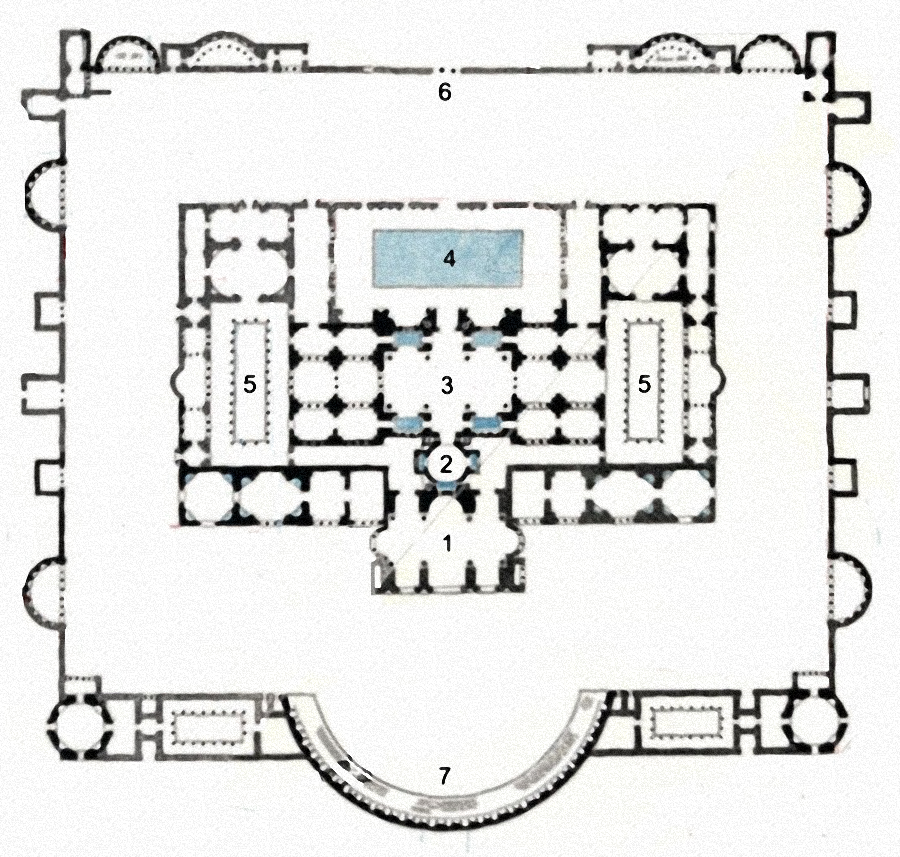

It could have been caused previously for any reason (i.e. failure of foundation). The answer that the Italian STORM pilot site of museum of Terme di Diocleziano (Diocletian Baths – Rome) is currently testing is based on a LIDAR scanner of the buildings.

The hypothetical scenario sees a rescue call to firefighters that arrive with their own LIDAR, scan the portion of the building damaged and compare their results with the data previously acquired by the museum managers. As it’s known LiDAR needs time and, mostly, large quantity of data storage, but a small portion of a building is much more manageable. So, even with a high definition setting, the procedure could offer a new possibility to improve the reliability of the assessment that rescuers have to do during operations.