What Really Happened in 1823? Uncovering the Gaps in the Saint Paul Basilica Fire Narrative

In investigating the causes of the fire at St. Paul Outside the Walls, the widely accepted theory of latent combustion faces a challenge: how to explain the delay of two to three hours between the accidental fall of embers and the appearance of flames? According to available documents, the time interval between the workers’ abandonment of the site and the discovery of the fire was quite long. The study conducted by two experts in the field of archiving and fire safety seeks to explain the facts narrated in the chronicles in the light of the most recent research on smoldering fires and the dynamics of wood combustion.

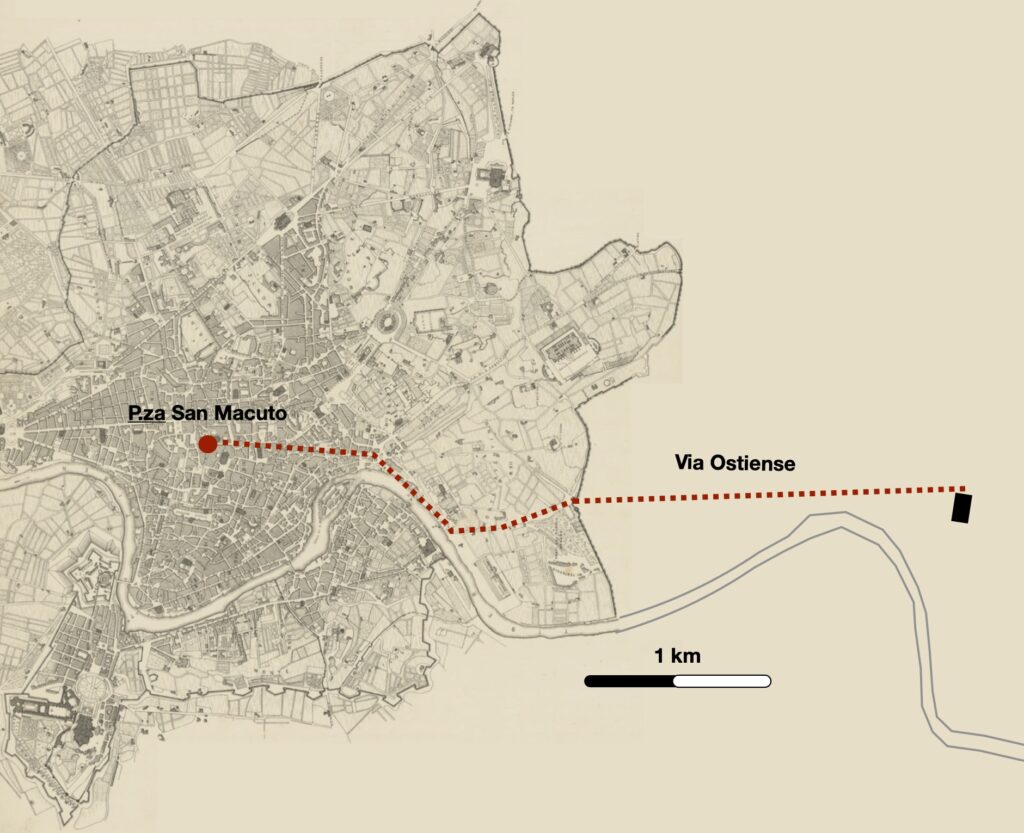

On the two-hundredth anniversary of the devastating fire that consumed much of the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls in Rome on July 16, 1823, numerous scholarly works have revisited the political and cultural context of the time, along with the ambitious reconstruction of what had been the most frequented basilica in the city. Yet, conspicuously absent from this body of scholarship is a critical, methodical investigation into the actual causes of the fire.

The prevailing narrative—formulated in the immediate aftermath of the disaster—has been largely accepted without question. Despite its many gaps and internal contradictions, it has remained the de facto explanation, passed down through generations with minimal scrutiny. These inconsistencies have never been thoroughly analyzed, and alternative hypotheses have been largely ignored or dismissed.

Addressing this scholarly void, the 2023 paper “The Fire of Saint Paul Outside the Walls: A Comprehensive Retrospective Scientific Investigation” re-examines contemporary sources and sheds light on the discrepancies embedded in the official account. Rather than accepting the cause of the fire as a settled matter, the study treats it as an unresolved enigma—one that warrants further inquiry and a broader consideration of possible explanations.

Method of the investigation

Consequently, the authors conducted an investigation in accordance with the scientific investigation methodologies outlined in the National Fire Protection Association standard NFPA 921-2021 “Guide for Fire and Explosion Investigations”.

Regarding the sources, newspaper accounts from the time of the fire attributed its cause from the very first hours to the negligence of workers responsible for repairing the roof or, according to some accounts, the gutters. A few days after the fire, the Diario di Roma also published an account of a fire on the roof of the Basilica of St. John Lateran due to the carelessness of the workers. The account, written by the monks of the Monastery attached to the Basilica, provided extensive details, linking the event to a dispute between bricklayers and tinsmiths.

The Gaps

The historical information presented in the document is based primarily on chronicles published between July 16 and 31, 1823, with additional references to various manuscript documents associated with them. In particular, details regarding the basilica and its condition were extracted from the writings of Nicola Maria Nicolai and Angelo Uggeri.

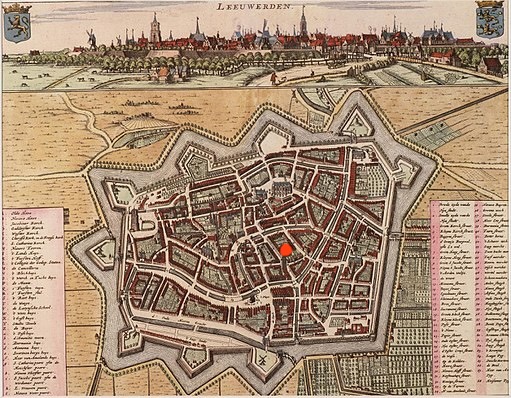

The Diario di Roma, a journal covering local and international issues, played a crucial role in providing insights into the state of the basilica and the damage inflicted by the fire. Issues dated July 16, 1823, and July 26, 1823, addressed these aspects. The magnitude of the damages becomes apparent through a multitude of images created by painters and engravers in the weeks immediately following the incident. These artists were drawn to the significance of the building and the gravity of the event, reflected in their works.

In unraveling the mysteries surrounding the 1823 fire at St. Paul Outside the Walls, the absence of direct testimonies from involved workers and the lack of information on the ongoing work make it challenging to definitively identify the ignition and propagation mechanisms.

Conclusions: Smouldering combustion is not the most probable hypothesis

To introduce hypotheses on the causes of fires in the field, the authors state that: “In the immediate aftermath of the fire, all the chronicles agree on the fact that maintenance work was underway on the roof, which was the only combustible structure of the building. Therefore, following the information provided by the chronicles, the main and secondary wooden framework of the roof is the construction element from which the authors have investigated the dynamics of the early stages of the fire. In general, the main causes of accidental ignition in a building where, like the basilica of 1823, there are were no systems fueled by electricity or by flammable or combustible materials, can be traced back to lightning or to the improper use of open flame lighting devices (torches, lamps, candles). No documents of the time report meteorological perturbations, while according to the anonymous “Postilla”, three people would have gone to the roof structure to carry out some surveys, an activity that after sunset would have needed the use of torches.”

Consequently, the authors propose that the analysis of the documents suggests two plausible scenarios. The first, which is the sole historical cause considered, is an accidental event involving the fall of burning coals during construction work. This resulted in a slow combustion process, consistent with the smouldering fire mechanism. The second scenario, which appears at least equally plausible, is a fire that commenced after the conclusion of the day’s work. In this instance, the ignition could have been accidental or intentional.

The lack of testimonies given by the directly involved workers and of information on the type of work in progress and on the extent of the fire at the time the fire was seen, prevent from corroborating both hypotheses.

According the authors, “The widely accepted theory of smouldering combustion faces challenges in explaining the delay between ember fall and the manifestation of flames, especially considering the timeframe from site abandonment to fire detection. Additionally, an alternative scenario proposed by the “Postilla anonima” suggests intentional acts after workers left the site, supported by the absence of workers’ names in chronicles and ongoing investigations weeks after the incident“.

However, critical details remain elusive in all the accounts: no one saw fit to explain what construction equipment was in use on the roof on the evening of the fire. Much less was the nature of the work in progress clearly clarified, and how burning coals could have fallen onto the wooden elements without the workers noticing. Finally, the total secrecy about the names of those responsible, released after little more than a day in prison, cannot be explained by such a serious crime.

Another gap illuminated by the study pertains to the progression of the fire’s development. Notably, the most significant sources (the two editions of the Diario di Roma) unequivocally assert that there was a period of at least four hours between the time when the workers dropped the materials that ignited the fire (around 20:00) and the subsequent discovery of the blaze (around 01:40 of the following day). These very sources specifically mention that there are accounts from identified individuals who observed in the meantime no signs of anything inside or outside the basilica, even during the night, when the flames would have been readily visible.

The sole type of mechanism that could plausibly account for this progression is a smouldering fire, which, however, necessitates a highly specific set of circumstances, including a light ventilation. Nevertheless, the sources unequivocally indicate that the prevailing winds were strong that evening, and consequently, the flames rapidly consumed the wooden structure of the roof.

As previously mentioned, another issue arises from the involuntary nature of the events that transpired at the conclusion of the work by the workers (or, at the very least, their lack of awareness that they had caused such substantial damage). A voluntary act or such a grave omission would have resulted in their arrest and subsequent trial, rather than the unusual detention of a few hours and the complete anonymity they were accorded.

In response to these uncertainties, the authors have tried to clarify the origins of the fire by juxtaposing historical sources with recent research results on the mechanisms of ignition and propagation of wood combustion.

Considerations Outside the Study

An intriguing aspect that has not been addressed by the authors of the publication is the climate prevailing in Europe during the time. This pertains to the 20th of July 1823 fire that engulfed the Church of the Espíritu Santo in Madrid, Spain. Although no victims were recorded on that occasion, the fire was started at the same time in different areas of the church, with many people present in the building, who were therefore exposed to extremely serious danger. In this regard, the soldiers who saved the Duke were awarded commemorative medals.

It is plausible that this act was orchestrated to assassinate the Duke of Angouleme, the commander of the French troops stationed in Spain. Certainly, this incident transpired during a particularly tumultuous period in Spanish history, marked by the culmination of a protracted conflict between monarchists and liberals. Although it remains a hypothesis lacking empirical support from sources or documents, it is possible that the unusual timing of the fire in Madrid, occurring four days after the fire at St. Paul’s in Rome, could have prompted Roman security authorities to suspect a plot to destroy Catholic places of worship. This hypothesis could potentially explain the severe measures adopted shortly after the fire to protect St. Peter’s Basilica and other churches in Rome.

More on the context of St. Paul fire

- Professor Richard Wittman’s upcoming book “Rebuilding St. Paul’s Outside the Walls – Architecture and the Catholic Revival in the 19th Century” scheduled for release in 2024

- Nicola Camerlenghi’s St. Paul’s Outside the Walls – A Roman Basilica, from Antiquity to the Modern Era.

- Reconstruction of the St Paul outside the Walls Basilica