Wildfires burn Korean 7th-century temple

On March 26th, 2025, major fires in South Korea – North Gyeongsang Province – have razed the ancient Gounsa Temple and Unrsamsa Temple in Uiseong, which dates back to the Silla Dynasty and is over 1,000 years old.

The national treasures housed in the temple had been relocated earlier. The temple had already been destroyed by fire in 1835 and rebuilt.

The blaze, fanned by strong winds, is putting the UNESCO World Heritage site Andong Hahoe Folk Village and the UNESCO site Byeongsanseowon Confucian Academy (the most common educational institutions of Korea during the Joseon Dynasty) at risk.

In both cases the structure in combustible materials and the proximity of vegetation to the buildings can constitute a serious critical element in the weather-climate conditions described.

The recent images from South Korea depicting the charred remnants of Unramsa Temple are heartbreaking. This tragedy is a severely damaging Korean culture, and, to promote fire safety for cultural heritage, it’s vital we understand not just that it happened, but how and why to mitigate such events in the future.

What can be learnt after the fires

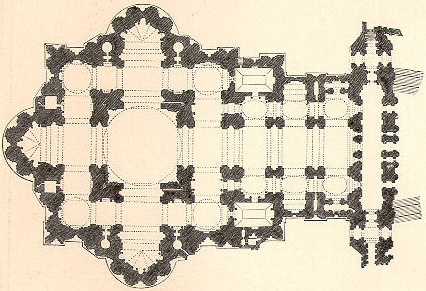

Unramsa, and temples constructed during that era, represented a specific approach to timber architecture, deeply rooted in Buddhist principles and adapted to the Korean climate and landscape. The construction methods, while sophisticated for their time, inherently presented vulnerabilities to fire. Traditional Korean temples rarely employed nails or screws; rather, the primary connections relied on complex joinery systems – geonmat (bracket supports) and jigum (supporting brackets) – holding timbers together. These interlocking wooden components, painstakingly carved and precisely fitted, formed the skeletal structure.

The foundation generally consisted of a layer of crushed stones laid directly onto the ground and sometimes incorporating a stone base to act as a plinth. Load-bearing pillars, typically substantial squared timbers, rose directly from this foundation. The roof structure, a defining feature of Korean architecture, was a complex system of rafters, purlins, and crossbeams creating deep eaves. This large roof not only provided shade and rain protection, but the deep overhang also served a symbolic purpose, mirroring mountains and protecting the sacred space it contained.

Materially, these temples were predominantly constructed from wood. Pine, fir, and oak were commonly used for the structural elements, with finer materials like larch or cedar utilized for intricate detailing and decorative elements. Roofs were covered with giwa – traditional Korean clay roof tiles which were relatively fire-resistant, but also heavy.

Supporting these tiles was a substantial underlayer of wooden sheathing, often cedar which provided good weather resistance but was highly flammable. Interiors were often decorated with painted murals and intricate woodwork. Lacquer was used in many decorative features but it’s easily combustible.

So, what made Unramsa so vulnerable? While giwa tiles are considered fire-resistant, a fire can ignite through numerous other ways, and the very architecture of these temples acted to propagate flames rapidly.

In terms of the fire’s origin and spread within the temple complex, several factors likely contributed. Firstly, the dry conditions reported in the region preceding the wildfire greatly increased the surrounding vegetation’s flammability. A nearby brush fire, possibly started by human activity or from lightning, could have readily jumped to the temple if wind conditions were favorable. Even a minor spark landing on the highly flammable wooden sheathing under the giwa tiles could have initiated a slow-burning, insidious fire.

However it is possible that the fire’s spread was amplified by several elements inherent to the temple’s design. The large, exposed wooden structure is essentially tinder; once ignition occurred, it would have rapidly fueled intense heat. The intricate joinery, while brilliant in its design, creates numerous cavities and hidden spaces within the structural framework. Those spaces act as chimneys, accelerating the fire’s spread throughout the building. A lack of modern fire retardants or fire breaks created a conducive path for flames to spread through the complex.

The air gaps underneath the roof tiles, and within the wall construction also allowed embers to be readily carried by the wind, igniting further blazes. If, as appears likely, this was a fast-moving wildfire with intense radiant heat, the external heat could have caused surface charring, then ignition of exposed wood on the exterior of the building.

This devastating event underscores critical gaps in cultural heritage protection. Preventative measures like vegetation management around sacred sites are essential. However, for existing structures like Unramsa, sensitive retrofitting strategies are needed. Fire-retardant coatings and, where possibile, fire suppression systems that minimize impact on the historic fabric, and potentially creating fire breaks within the temple complex must become priorities.

Authorities have deployed massive resources to fight the blazes, with 77 helicopters and more than 3,000 personnel deployed. However, strong winds and dry conditions are complicating containment efforts for the fourth consecutive day. Over 12,500 hectares were affected by the Uiseong fire, making it the third largest forest fire in the country’s history.

Other fires that broke out simultaneously in different areas of the country were brought under greater control. Unfortunately, the fires in southeastern South Korea have left five people dead and injured others.