Japan Cultural Heritage Resilience against Natural and Man-made Disasters

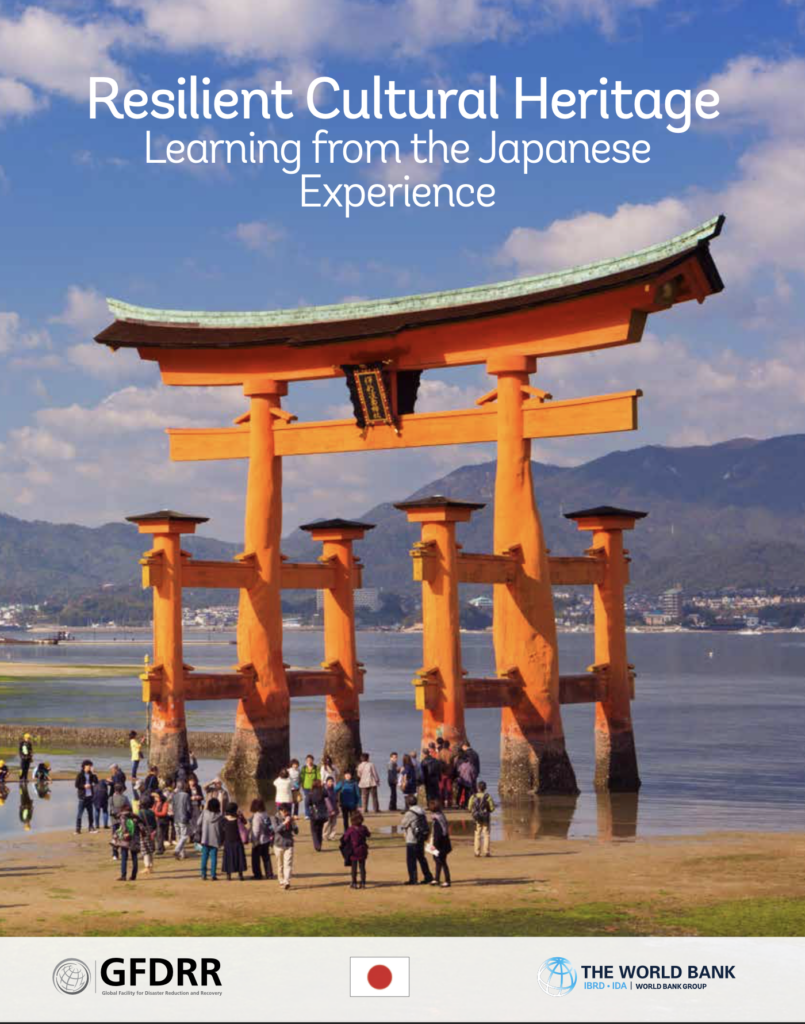

Japan has developed extensive experience in disaster risk management (DRM) for cultural heritage (CH) through years of history and disasters, and the country continues to learn from new challenges. An insight of the legislative approach to this complex aspect of the national identity has been published in the 2020 publication “Resilient Cultural Heritage Learning from the Japanese Experience” from Japan—World Bank Program for Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Management in Developing Countries.

The country’s vast and complex heritage and the immense threats it faces have prompted communities and authorities to develop and adapt their efforts to local contexts. Japan has over 2,000 active faults and 111 active volcanoes, which cause frequent earthquakes. In addition, many buildings are made of wood, making them vulnerable to fires. Consequently, earthquake and fire risks are always taken into consideration when discussing DRM in Japan.

CH Disaster Risk management in Japan

The first step in disaster risk management for cultural heritage in Japan is the identification and classification of cultural heritage into six different categories: Tangible Cultural Properties, Intangible Cultural Properties, Folk Cultural Properties, Monuments, Cultural Landscapes, and Groups of Traditional Buildings. These classifications are the basis on which the country manages the protection of CH. The Japanese government uses a designation/selection/registration system to identify and protect cultural properties. This system helps identify and adopt the best protection measures for each cultural property according to its category, and provides subsidies to preserve, repair, or make its structure resistant to disasters.

Japan has established institutional frameworks for both disaster risk management and cultural heritage. The Agency for Cultural Affairs (ACA) is the key institution responsible for the protection and management of CH, including DRM measures and actions. The ACA provides guidelines for the development of local DRM plans, manuals, training, exercises, and communications, as well as for the dissemination of knowledge. Local governments and cultural property owners are responsible for implementing measures to monitor and stabilize slopes, including the construction of retaining walls, monitoring groundwater flow, and building drainage facilities. ACA also works with various partner organizations, such as the network of school boards within local governments and the Japan Association of Architects for Monument Preservation (JACAM), to conduct post-disaster assessments and investigations and plan repair and restoration work.

Japan integrates DRM measures into every stage of the cultural heritage protection and management process. For example, risk mitigation measures are installed during the maintenance phase to prepare for future threats, and alterations to the current state can be considered during repairs if damage is found due to threats. DRM efforts focus on countermeasures for earthquake and fire hazards, as well as fire prevention systems. ACA promotes fire prevention measures, such as automatic fire alarm systems, fire-fighting equipment, and lightning rods.

Japan also recognizes the importance of community engagement in disaster risk management for cultural heritage. Communities are involved in identifying risks, developing mitigation measures, and in resilient recovery processes. For example, the Disaster Imagination Game (DIG) method is used to engage communities in identifying risks and developing preparedness measures. There are also examples of communities working with religious institutions to reduce fire risks, such as in the cases of Kiyomizu-dera and Myoshin-ji.

Japan’s experience in disaster risk management for cultural heritage provides valuable insights to other countries. It emphasizes the importance of:

- A strong institutional framework.

- A comprehensive cultural heritage identification and classification system.

- The integration of DRM measures into every stage of the heritage protection and management process.

- Community involvement.

Japan’s approach demonstrates that cultural heritage protection is a collective effort that requires collaboration between government, communities, and experts.

History of CH protection in Japan

Japan’s cultural heritage protection system has undergone significant evolution since World War II, shaped by epochal events, socioeconomic changes, and emerging social needs. An interesting insight by Emiko Kakiuchi “Cultural Heritage Protection System in Japan – Current issues and prospects for the future” summarizes the regulatory path on the protection of cultural heritage that followed the disasters of World War II

Before World War II, heritage protection was primarily a national government initiative, focused on the preservation of ancient artifacts and temple and shrine buildings. The emphasis later shifted to a nationalistic motivation with the push for modernization during the Meiji Restoration in 1868. However, during and after World War II, heritage protection efforts came to a near-halt.

In 1950, the burning of Horyu-ji Temple, one of the oldest wooden structures in Japan, sparked strong national sentiment for cultural protection. This event led to the enactment of the Cultural Property Protection Act (LPCP) that same year. This law introduced several changes:

- Integration of pre-war tangible heritage with the concept of intangible cultural heritage. This expanded the scope of protection to include not only artifacts and buildings, but also performing arts, music, and traditional crafts.

- Authorization of local governments to designate their own cultural assets. This marked a shift from a centralized to a more decentralized system, recognizing the importance of local heritage and involving communities in protection efforts.

The 1960s and 1970s saw Japan face the challenges of rapid economic development and its negative impacts on cultural heritage. Uncontrolled urbanization, over-centralization, and depopulation of rural areas led to the destruction of historic towns and the deterioration of the environment surrounding traditional buildings. The loss of folk arts, traditional costumes, and buried cultural assets due to structural changes in the economy and modernization of lifestyles further highlighted the need for a more comprehensive approach to heritage protection.

As a result, several legal measures were enacted to address these concerns:

- The Ancient Capitals Preservation Act (LPAC) was enacted in 1966 to protect not only historic buildings but also historic landscapes in ancient national capitals such as Kamakura, Kyoto, and Nara.

- Local governments began issuing ordinances to protect traditional landscapes, culminating in the revision of the LPCP in 1975.

- The revised LPCP introduced several important changes, including:

- The introduction of “Groups of Traditional Buildings” as a new category of cultural properties, allowing for the protection of entire historic districts.

- Strengthened measures for the protection of Buried Cultural Properties.

- The inclusion of Conservation Techniques for Cultural Properties and Folk Cultural Properties, including Folk Performing Arts.

From the 1980s onwards, Japan has witnessed a growing appreciation for local culture and identity. Cultural properties have been increasingly recognized as essential to social cohesion and valuable resources for local development, particularly through cultural tourism.

This change in attitude has led to further developments in the heritage protection system:

- Japan’s ratification of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention in 1992 led to the inscription of Japanese sites on the World Heritage List, raising awareness of the importance of cultural properties and their surrounding environment.

- The revision of the LPCP in 1996 introduced the registration of traditional buildings as a more moderate protection measure, complementing the existing designation system. This measure aimed to safeguard landmark buildings from the modern period at risk of demolition due to development.

Cultural heritage and development

In the 21st century, attention has shifted to a closer link between cultural heritage and development. The promulgation of the Basic Law for the Promotion of Culture and the Arts in 2001 reflects a broad social consensus on the importance of culture and calls for support for cultural activities from various actors, including local governments, non-profit organizations, businesses and citizens. As a result, the heritage protection system has continued to evolve:

– The introduction of “Cultural Landscapes” as a new category in the LPCP in 2004 recognized the value of cultural landscapes created through human interaction with the natural environment.

– More moderate forms of classification, such as selection and registration, introduced in 1975 and 1996 respectively, have broadened the range of protection measures available.

– The registration system was extended in 2004 to include Monuments and Folk Cultural Properties.

– The evolution of the cultural heritage protection system in Japan after World War II demonstrates a dynamic path shaped by critical events, socioeconomic changes, and growing awareness of the value of cultural heritage. The system has expanded from its initial focus on the conservation of tangible assets to embrace intangible heritage, cultural landscapes, and community involvement. This evolution reflects a deep appreciation of cultural heritage as an integral part of Japan’s identity, social cohesion and sustainable development.