The Arson Threat to Historical Buildings and Built Heritage

Arson has been in history and continues to pose a serious risk to historic and cultural buildings. In fact, the greater vulnerability to fire that these often present is added to the symbolic value they have, which can often be the cause of hostile actions. Below we publish a short text summarized by the COST Action C17 – Built Heritage: Fire Loss to Historic Buildings in its Final Report Part 1 (pages 90-92), which collected some data of still current interest in the period. The growth of arson globally cannot be precisely summarized, due to statistical variations, but the persistence and perhaps growth in many developed countries of arson shows a growing problem.

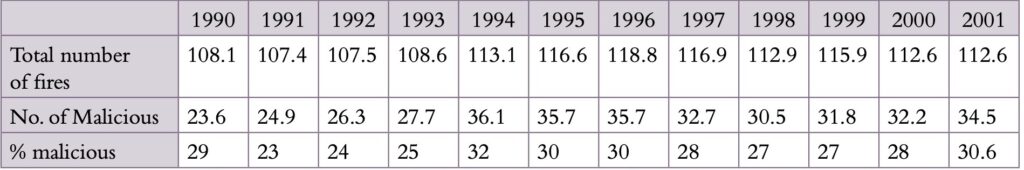

According to the CTIF (Center of Fire Statistics) in eight selected countries [Canada, Germany, New Zealand, Russia, South Korea, Japan, the United States and the United Kingdom] between 1993 and 1999, intentional fires accounted for 18 percent of all building and structure fires

The implication of this data is also that in many contexts a significant part of the built environment contains historic sites and that some property classifications (such as religious buildings) are subject to regular attacks. The following table, published in the report, indicates significant numbers in this regard.

La Fenice Venice, Italy – On 29 January 1996 a fire happened as the Teatro La Fenice was being renovated. The subsequent rebuilding did not go according to plan and the original German-Italian consortium of Holzmann-Romagnoli had asked for supplementary and fee waivers before the work was re-tendered. On Friday 30 March 2001, a court in Venice found two electricians guilty of setting fire to La Fenice opera house in the city in 1996. They were found to have set the building ablaze because their company was facing heavy fines over delays in repair work. The rebuilding of the theatre, for which Giuseppi Verdi composed several operas, was delayed. It was re-opened in 2004.

Sinsheim Mosque, Germany – On the 18 November 2004 unknown individuals threw a Molotov cocktail at a mosque near Heidelberg in Germany. A glass bottle filled with flammable liquid was tossed against the entrance of the Sinsheim mosque. The fire was discovered and extinguished after it caused around €10,000 damage to the wooden door and the glass window.

Wooden Churches, Poland – In Poland, wooden church were found to be particularly at risk. Between 1999 and 2000, 50 churches burnt down. The most frequent cause of fire is not damage to electric installations, but a fire lit deliberately. Poland has a substantial amount of sacred wooden architecture, which make an important, often unique, contribution to European heritage. It consists in part of wooden churches, built between the C14 and C19, mainly Catholic, but there are also other churches, including Protestant, Orthodox, Catholic-orthodox, Dukhobor, Jewish and Mariavites churches. Wooden religious architecture also includes chapels, belfries and morgues. The scale of the task is significant, given that presently there are 2,785 items of religious wooden architecture in Poland and six of them (from the C15 and C16) are on the World Heritage List.

The Arson Threat

The threat of arson poses a significant threat to heritage structures around the world, resulting from diverse motivations ranging from economic fraud to cultural disillusionment. Offenders may employ sophisticated methods involving science and technology, or resort to impulsive attacks using readily available materials. Regardless of the underlying cause, the outcome often leads to complete destruction of both the physical structure and its contents. Real-life examples highlight the broad spectrum of objectives, from internationally renowned monuments to more generalized building typologies, underlining the gravity of the challenge at hand. While various causes and solutions to combat arson exist, heritage buildings face unique vulnerabilities that amplify the risk of deliberate attacks:

- Their construction materials, notably wood, may be particularly susceptible to fire.

- Structural modifications can create voids that facilitate the spread of fire.

- Concealed building services and features may increase the likelihood of undetected fires.

- Issues such as unclear ownership and economic constraints may hamper effective risk management.

- Hazardous materials on industrial or military heritage sites pose additional threats.

- Arson may be used to conceal other criminal activities such as smuggling or theft.

Addressing this threat demands a concerted effort from the heritage community to develop a sustainable strategy supported internationally, especially given the limited legal requirements for fire safety in heritage buildings across many European countries. Initiatives like the Cost Action C17 have expanded their focus to include arson reduction and protection, conducting research to identify national risk profiles and implement preventive measures. Sharing best practices can enhance sustainability and bolster responses to this growing concern.

Terrorism

(Tasnim News Agency, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

In addition to traditional threats from vandals and criminals, the specter of terrorism, particularly from extremist factions, looms large over heritage sites and public gathering places. The shift in tactics post-9/11 has seen major landmarks targeted for their symbolic value, compounded by the anonymity and international recognition they offer perpetrators. While lethal terrorist incidents remain relatively rare, the economic and societal impact can be substantial, particularly in heavily frequented areas. In this regard the report clarifies that Lethal events are often infrequent, and in comparison to the routinely accepted loss of life in any country, are of a low order of magnitude. Usually, the risk is simply disruptive, as with left luggage (one example is 2.5 million emergency calls to unattended bags in a 10-year period in a transport environment, with no active explosive devices found).

The evolving nature of terrorism, influenced by transnational ideologies and localized extremism, poses challenges for defenders who must anticipate threats in advance. Coordinated efforts encompassing risk evaluation, crisis management, and threat monitoring are essential. Identifying high-risk sites and potential scenarios, such as attacks on religious institutions, is paramount in a landscape where total protection is impractical.

Conclusion

The pressing need to assess and mitigate risks posed by vandalism, criminality, and terrorism to heritage sites calls for collective action and intelligence sharing. Expanding the mandate of initiatives like the Cost Action C17 can facilitate this endeavor, requiring initial financial support to delineate the scope and secure funding for comprehensive action plans, ultimately safeguarding our shared cultural heritage.