Treating Debris of Historical Value after an Earthquake

Over the last thousand years, at least 2,500 earthquakes with a magnitude greater than 5 have hit Italy. At least 15 have had catastrophic consequences, causing over 120,000 victims.

Such tragedies have led Italy to develop a cutting-edge methodology for the management, selection and reuse of debris of cultural interest. This approach, has been illustrated in the article “Earthquake debris of cultural interest: the Italian methodology for their management, selection and reuse” published in the December 2024 Issue of the Technical bulletin of the PROCULTHER-NET 2 Project.

Following the 2016 earthquake, the methodology adopted by the Cultural Heritage experts is based on a classification of debris into three types:

- Type A: debris with a high historical-artistic value, such as fragments of frescoes, sculptures, decorative architectural elements.

- Type B: debris from historical buildings and of architectural value, potentially reusable for reconstruction.

- Type C: common debris, not of cultural interest.

A significant example of the application of this methodology is the case of the historic center of Amatrice. Here, due to the high level of destruction, a systematic plan for the removal of the rubble was necessary, entrusted to the Lazio Region through the Special Offices for Reconstruction (USR). The historic center was divided into “lots” and “quadrants” to facilitate the removal and sorting of the debris.

The Ministry of Culture was directly responsible for the management of type A debris, transporting it to dedicated depots for selection and future reuse. A fundamental role was played by the Fire Brigade, Civil Protection volunteers and professionals in the sector, who collaborated to identify and recover valuable elements from the rubble.

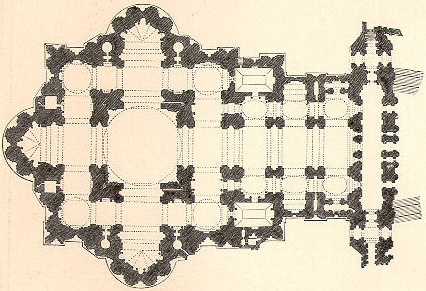

Another emblematic case is that of the Church of San Salvatore in Campi, near Norcia. The church, severely damaged by the earthquake, had a large amount of debris and the difficulty of accessing the site made it necessary to develop a specific intervention methodology. In this case, the intervention, coordinated by the Central Institute for Restoration (ICR) and the Superintendence for Umbria, was divided into several phases:

- Securing the structure and recovering the decorative elements.

- Cataloguing the finds using a grid system based on the discovery area.

- Transfer of the finds to a temporary storage area.

- Reassembly of the stone structure of the iconostasis balustrade and reorganization of the fresco fragments.

Thanks to this methodology, it was possible to recover almost all the authentic material of the church, allowing for a deep reflection on how and what to reconstruct. The in situ reconstruction project of the iconostasis aims to create an architecture that is seismically resistant and independent from the rest of the church, with the introduction of reversible and distinguishable structural elements.

The approach to the management of debris of cultural interest adopted in 2016 represents a model of excellence at an international level. The multidisciplinary approach, the collaboration between institutions and the active participation of local communities have made it possible to transform the rubble of the earthquake into an opportunity for the rebirth of the Italian cultural heritage.

Although focusing on the 2016 earthquake, the technical bulletin highlights how this methodology can be applied to any other type of emergency. The importance of debris management for the reconstruction of the urban and social fabric is a highly topical issue, which requires careful planning and the creation of structures dedicated to the storage and reuse of recovered materials.

The conservation of debris in situ is essential to preserve the memory of the pre-existing urban fabric and to facilitate the reuse of materials in reconstruction. As the case of Amatrice demonstrates, the rush to give a rapid response to reconstruction expectations can sometimes lead to decisions that neglect the importance of historical memory.

The recovery of the Civic Tower of Amatrice, with the reuse of type B debris, and the restoration of the Church of San Salvatore in Campi, with the recovery of type A debris, are concrete examples of the effectiveness of the Italian methodology. The progress made compared to previous earthquakes is significant: debris management has produced remarkable results in the recovery of the cultural heritage of the affected communities, providing a fundamental contribution to their material reconstruction and to the conservation of their intangible heritage.

We would like to underline the importance of the PROCULTHER-NET 2 article, which deals with an extremely important aspect which is little covered in the sources concerning the management of emergencies and post-emergencies in which historic buildings are involved.

Assisi’s case: the importance of protecting debris

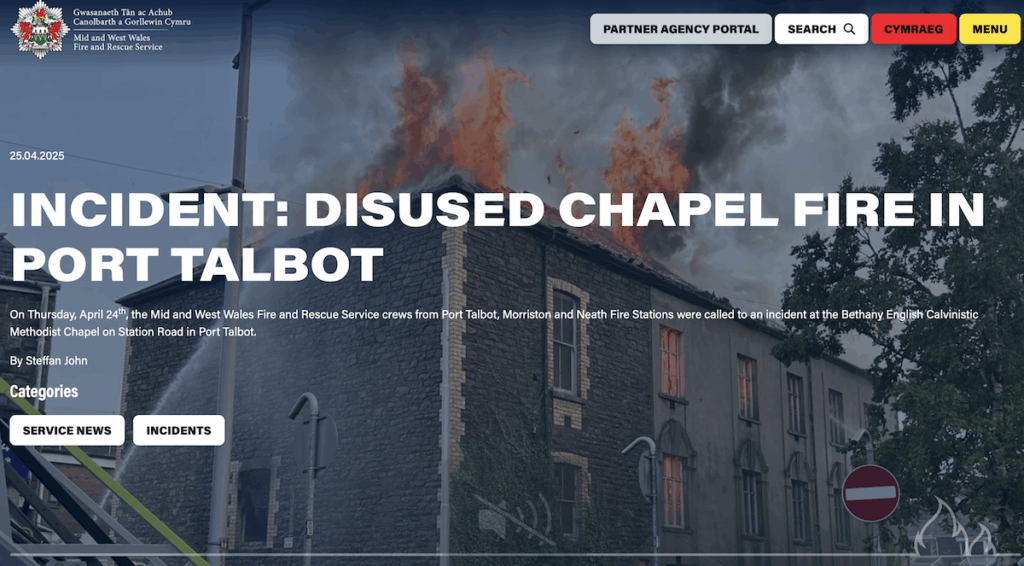

Following the damage caused by the September 26, 1997 earthquake that affected a large area of central Italy, the Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi suffered serious damage, including the collapse of a vault with important frescoes.

Immediately after the 1997 earthquake, a gigantic and unprecedented operation was started to recover the fragments and recompose the frescoes.

The result of this staggering operation highlights the importance of recovering the rubble in an appropriate manner. Below are the highlights of the restoration, divided by interventions account of the article by Giuseppe Basile.

The restoration of the frescoes of the Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi was a complex operation that involved several professional figures and required a precise methodological approach.

Consolidation and cleaning interventions

- Lower Basilica: Interventions were carried out to re-adhere the plaster in correspondence with the Vela della Povertà and the Chapel of San Giovanni.

- Upper Basilica: Emergency interventions in the collapsed or damaged vault areas, such as in correspondence with the faces of Christ and the Madonna by Jacopo Torriti.

- Consolidation of the vault from below, with filling of the lesions and microfractures using a special mortar developed in the laboratory. This work involved the employment of 70 restorers for 4 months, followed by the introduction of the same mortar from the extrados, carried out by specialized construction personnel under the guidance of the restorers.

- Cleaning of the paintings, in particular the Stories of St. Francis by Giotto, covered by a thick layer of dust due to the collapse of the vault. This delicate operation took 50 restorers 6 months to complete.

Reintegration of the gaps

The gaps in the vault were integrated using the optical and chromatic lowering method of the plaster, so as not to disturb the readability of the images without adding original material. This work took 8 months and involved 60 restorers.

Recovery and relocation of the fragments

- Collapsed sails. Residual wall decorations of the fragments of the collapsed sails (including the Christ of the sail of St. Jerome) were removed, as a pair of Saints in the entrance arch for their reconstruction in the laboratory. The fragments were then applied to a new support and relocated to the vault.

- Recovery, consolidation and relocation. A part of the original bricks with fresco fragments still attached, corresponding to the lower part of the two collapsed transverse arches, was recovered, consolidated and relocated .

- Mural painting fragments. Approximately 300,000 fragments of mural painting from the rubble were recovered and selected. The recovery was carried out by the Fire Brigade with the help of restorers and art historians, while the selection was carried out by volunteers guided by restorers and conservators.

- Fragments of the 8 Saints, of the transverse rib and of the sail of San Girolamo. Such fragments were reassembled, restored and relocated as, subsequently, the sail of San Matteo. The starry sail was subjected only to an optical-tonal lowering of the plaster.

Digital acquisition

Digital acquisition involved 120,000 fragments relating to the sail of San Matteo by Cimabue. A virtual archive and development of software for computer-assisted reassembly was created.

Restoration methodology

The methodological approach was not to mimetically reintegrate the missing parts, but to preserve the authenticity of the work. So, the optical-tonal lowering of the gaps was chosen so as not to disturb the readability of the images without adding anything to the original material.

For the reassembly of the fragments, the sample intervention method was followed, starting with Saints Rufino and Vittorino. Moreover, the decision to relocate the original fragments, instead of resorting to copies or reconstructions, was supported by the community of the Friars of the Sacred Convent.

Organizational aspects

- Responsibility. Responsibility for the interventions on the figurative heritage was entrusted to the ICR (Central Institute for Restoration), given its long tradition of interventions in the Basilica and its expertise in similar situations.

- Professionals and academic contributions. The work was carried out by professional restorers, university scholarship holders and volunteers, with particular attention to staff training.

- Restoration site. The restoration was managed by a complex construction site, with an internal structure divided between the restoration of the mural paintings in situ and the reassembly of the fragments. This involved coordination between different professional figures.

Operational issues

Managing the relationship between interventions on the building and interventions on the wall decorations was one of the greatest difficulties, with the need to assess the risks for the works of art in advance. Another aspect that influenced the duration of the restoration is the fact that the needs of worship and representativeness of the Basilica had to be taken into account, which influenced the times of progress of the works.

Results and consequences

The activities carried out, in addition to the restoration of the damaged parts, allowed to achieve results that were not initially foreseen.

- The use of oil as a binder by the Master Oltremontano was discovered, which confirmed the chronological priority of his pictorial decoration.

- The mechanism of alteration of lead or mercury-based pigments was clarified, explaining why they alter in Cimabue and Giotto but not in the Master Oltremontano.

- Publications, seminars, exhibitions and educational activities were created to communicate the restoration activities to the public.

- Software was developed for the reassembly of the fragments.

This brief summary highlights the breadth and complexity of the restoration of the frescoes of Assisi, an operation that required years of work and the commitment of numerous experts. It should not be forgotten, however, that the prerequisite for this operation was the care and conservation of the debris, including the smaller ones that, carefully collected and adequately preserved, allowed us to imagine and realize the subsequent reconstruction.